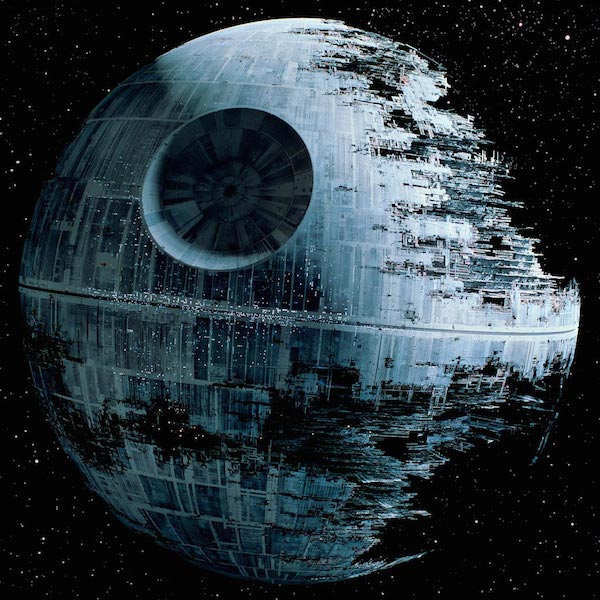

Google Fiber Is A Death Star

Now witness the firepower of this

fully armed and operational battle station

wireless antenna.

Photo credit: Star Wars Wikia.

Google Fiber’s big announcement last week, that they’re going to “pause” the rollout of Google Fiber in new cities, in combination with the resignation of CEO Craig Barratt, led to a lot of speculation that this particular letter in the Alphabet is in trouble. Everyone from Ars Technica to The Washington Post had some fun with this story. So why not us?

We don’t want to bore you, so we offer you a different take. Google Fiber isn’t in trouble: in fact, it’s poised to completely disrupt the ISP market. In short, Google Fiber is the Death Star from Return of the Jedi.

Before we get into the whole Death Star thing, let’s consider some of the various theories about what’s really going on behind the scenes.

Google Is Losing Too Much Money

Wait, hold on for a moment, while I catch my breath from laughing hysterically.

Let’s see. Google made nearly $5B in profit in the third quarter of 2016 alone. It’s sitting on more $78B in liquid assets. Google isn’t worried about the near-term profitability of Google Fiber, nor the barriers to entry into the market. And neither are their investors, who had virtually no reaction to the announcement. If anything, Google’s biggest problem is coming up with ways to generate a reasonable return on capital, exactly because it’s sitting on so much cash and there are only so many ways you can profitably invest it. And unlike the CEOs of Google’s competitors in this space, Larry Page and Sergei Brin aren’t worried about the value of their stock options, and their investors aren’t in it for the dividend checks.

The ISP Business Is Too Messy

Let’s also dispense with the whole they-didn’t-know-what-they-were-getting-into hypothesis. I’m sure it’s been a messy business, but Google has already successfully launched service in eight cities and there are no plans to discontinue service. And why would they? They have a half-million subscribers, with a minimum subscription of $50/month, so that’s at least a $300M a year business already, in just four years. Keep in mind, Comcast alone does $75B a year, in spite dismal customer satisfaction ratings. Put another way, Google has made rapid inroads into market with high barriers-to-entry and massive upside, which is an ideal combo when the problem you’re solving is return on capital.

And while blog posts from resigning CEOs aren’t worth the bandwidth they’re consuming, perhaps it’s worth considering Barrett’s own words:

…our business is solid: our subscriber base and revenue are growing quickly, and we expect that growth to continue.

That’s not exactly ambiguous.

There’s Insufficient Demand For Gigabit Internet

Again, laughing hysterically here — please hold.

Okay, I’m back. Vox’s Ariel Stulberg seems to think this is a thing:

The basic issue is that even the most bandwidth-hungry of today’s applications use far, far less than a gigabit … If you want Netflix’s highest-quality streaming, called Ultra HD, that requires 25 Mbps. So a gigabit connection would allow you to stream 40 Ultra HD videos at a time.

Forty HD videos at a time. Woooooooooo!

Seriously, though, this confuses supply with demand. Netflix had no choice but to squeeze their service into 25 Mbps because that’s all that’s available. It’s the supply of bandwidth that’s limited, not the demand. The true demand is unknown because of the limited supply.

But The Layoffs?

But what about the layoffs? you ask. I’ll come back to that.

Suffice to say for now, the entire Google-Fiber-Is-In-Trouble narrative is based on anonymous sources and storylines from the 1980s television show Dallas.

Photons Versus Shovels

The real explanation is Google believes they have a better way to disrupt the ISP market with wireless technology. In fact, I’m confident this was always the plan. Google Fiber was launched in 2010, when high-bandwidth wireless solutions were already coming to market. Maybe not a coincidence.

Google’s recent blog post came less than a month after another post, which was largely ignored but probably more significant. In early October, Google announced that their acquisition of WebPass was complete. Barratt himself has a background in wireless technology. And he brought over Dennis Kish, who also has a background in wireless technology, from Qualcomm, the company that acquired Barratt’s startup, Atheros. Although Barratt is stepping down as CEO, he’s staying on as an advisor to none other than Larry Page, in an entity called, um, L.

Translation: Barratt’s job was to identify a wireless solution for Google Fiber. With the acquisition of WebPass, that job is done. Kish’s job is to oversee the integration of WebPass and Fiber, while Barratt keeps hunting for complementary acquisitions, like (for example) Artemis Networks.

Wait, what? Who’s Artemis?

Self-Replicating Networks

Artemis Networks is another Steve Perlman venture, he of OnLive fame, and the developer of an antenna technology that, in combination with WebPass line-of-sight antennas, will give Google the ability to dramatically accelerate the rollout of Google Fiber in new cities, while simultaneously expanding it those it already serves. And WebPass has already been experimenting with Artemis technology in the field. My guess is that it works and those experiments are part of the appeal of acquiring WebPass.

Of course, Google Fiber may not need to acquire Artemis Networks. They’ve already been experimenting with ways to get wireless routers into your home. Nest, their home automation solution is one, and OnHub is another. One way or another, Google will find ways to entice consumers to put Artemis-like mesh wireless technology into their homes.

So imagine this: you lay some fiber. Fine. Can’t get around that. But you don’t need as much because you have these point-to-point antennas from Web Pass. That gives you a way to bootstrap the service in high-density urban areas. You issue these mesh antennas as part of your standard install. Or maybe there’s already a Nest or OnHub device or whatever. Your service radius expands with each device, allowing you to expand into areas where you would have otherwise needed fiber (because there’s no line-of-sight for wireless antennas). The more people you sign up, the larger the service radius, until you’ve got an entire city covered. All with only the fiber needed for your bootstrap sites.

Even better, your cost of doing business is dramatically reduced because these mesh devices are your infrastructure. In fact, maybe you’re costs are so low, competitors are forced to operate a loss to keep from losing subscribers.

This technology, in the hands of a company with Google’s resources, is already compelling. But, given that they’ve already proven they can operate as an ISP at scale (half-a-million subscribers), the only reasonable conclusion is that Google is positioned to become the market leader within five years.

Juicing The Market

I’m among those who believe Google entered this business to force the telecoms and cable companies to invest in their networks. Prior to Google’s entry into the market, they were effectively colluding to minimize capital expenditures in favor of hitting profitability targets favored by their investors. Grandma got her dividend check and the CEO could buy that nice villa in Lake Como. But Google effectively prints money when people use the Web, and they need bandwidth to do that, so Google needed to shake things up.

Back to the whole supply versus demand question. Gigabit Internet opens up whole new vistas of possible applications, ranging from gaming to wall murals streaming Game Of Thrones. Google has myriad ways to monetize that usage, ranging from search to Gmail to Android. If the telecos and cable companies weren’t going to offer faster speeds, Google would, and, in the process, force their hands. And it worked. The moment Google announces service in a new city, magically, existing providers improve their service.

(Google did the same thing with the Chrome browser. Both the Mozilla and Microsoft browser efforts were stagnating. At the time, Chrome was seen as an attempt by Google to gain a Microsoft-like grip on the software industry, but their business model doesn’t depend on switching costs as Microsoft’s did. All they need is for more people to use the Web and they make more money.)

Stocking Up On Xanax

There is no way Google is dumb enough to just sit on nearly $80B in assets when they could be investing it in ways that are sure to grow their revenues across all of Google. And, in fact, that’s not what’s happening. They’re going to invest that cash to prove the viability of Gigabit Internet and force everyone else to play catch up. If the suits at AT&T, Time Warner Cable (oh, sorry, Spectrum), or Comcast are breathing a sigh of relief because of the fan fiction produced by a site called The Information (really?), they’re doomed to disappointment. They should instead be stocking their supplies of Xanax and 18-year old Scotch and updating the Gulfstream lease. (Hint: go for the long-term lease.)

Oh, Right, The Layoffs

But what about those layoffs? Doesn’t that always spell trouble? No, that spells acquisitions. There’s likely some overlap between WebPass and Google Fiber staff, and their may be more acquisitions to come. Google Fiber isn’t aiming to be a traditional ISP, they’re aiming to be an ISP whose coverage expands automatically with each signup, and the economics-and therefore staffing—may look quite different.

Google Gigabit?

Of course, this is all wild speculation. You should not invest your money based on what I write. I have no anonymous sources. (Well, I do, but they’re not talking, even though I paid for the drinks.) I have no stories of corporate power struggles or ruthless uber-rich executives, except for the ones I remember from Dallas. I don’t even have a GulfStream lease to renew. On the other hand, the last time a well-capitalized innovator took on a stagnating industry, we got the iPhone. So I’m going with Death Star. (Yes, I know it was destroyed in the end. Again. But, I mean, come on.)